Fabris is Dinamo’s jewel in the crown. The team would be lost without his goals. But there’s a problem: he’s egotistical, self-centred and anything but a team player. Sent off in a big match, he barely bats an eyelid. Slicking his hair back and suiting up in the dressing room, Fabris receives a bollocking from his coach. He’s heard it all before. “Fabris, you’re a bad influence on younger comrades,” the striker says mockingly before the coach can. “Fabris, you lack discipline. Fabris, you’re ruining the collective spirit.” Indeed, Dinamo’s No.9 is well aware he isn’t only letting his teammates down but the entire Physical Culture Movement.

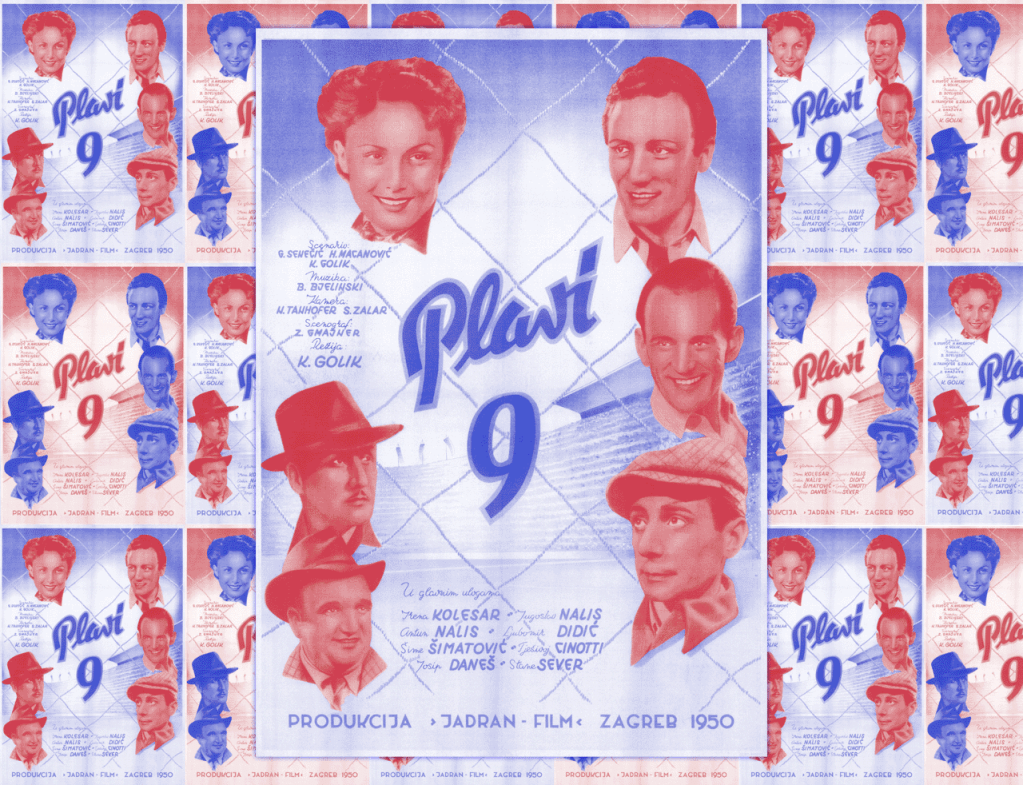

This is post-war Yugoslavia, after all, the setting of Croatian director Krešo Golik’s 1950 film Plavi 9 (Blue 9). The film was a big hit in Yugoslavia, where the newly established communist government had just powered up the propaganda machine, pushing its socialist doctrine via a slew of new artworks. Plavi 9 fitted the bill, the film’s communist messaging coalescing with quirks bound to attract big audiences: laughs, football and scantily clad girls. Part of the government’s agitprop was the Physical Culture Movement, a means to encourage the public to be physically active. The ill-disciplined Fabris is hardly the campaign’s poster boy. “Sport should form fine and firm characters,” Dinamo’s coach tells Fabris, threatening to replace him. Fabris scoffs at the notion, a finer goalscorer there isn’t in the land.

Enter Zdravko, the talented underwater welder and exciting young centre forward who plays for the local shipyard team. Dinamo secretly plan to replace Fabris with Zdravko. But when Fabris finds out, he sets about putting a spanner in the works. At the same time, some of Zdravko’s teammates and shipyard co-workers don’t want to lose him, and comedy ensues as the characters selfishly scheme to get their way. All the while, Zdravko is preoccupied with his courtship of Nena, a shipyard apprentice more concerned with competitive swimming than her studies, and for good reason: she is tipped to win the upcoming swimming championship. Zdravko and Nena are weighed down by the same dilemma: is it more important to be a good employee or to follow one’s sporting dreams?

Plavi 9 sets out to resolve this quandary. The film’s answer? Be a good employee and you will be allowed to chase your dreams. Zdravko and Nena both eventually choose work – a commitment to the collective – over individual sporting success, and of course their reward is the opportunity to do both, while the lazy and self-serving Fabris is ousted from the team. Such conspicuous ideological peddling wasn’t off-putting to audiences; the film offers more than just its dogmatic messaging, including most interestingly some exciting football scenes. Wide shots are taken from a real game, the crisp footage a fascinating historical document in itself, while the close-ups track dribbling feet and funny fan reactions. There’s plenty of comedy, much of which comes from the supporting characters: Fabris’ right-hand man (seemingly just a Dinamo fan who follows him around) and Zdravko’s pal Pjero serve up the biggest laughs as they conspire to sabotage one another’s plans. There’s romance, too: Fabris is also affectionate towards Nena, but she repeatedly rejects his advances. Stick to a hard-working boy, Nena, like Zdravko.

Once a hugely popular piece of propaganda, Plavi 9 has currently been logged as watched by only 34 Letterboxd users. A relatively prolific filmmaker, Golik went on to direct One Song a Day Takes Mischief Away (1970), one of Croatia’s most beloved films. But Plavi 9 is where it all started, both for Golik and the Yugoslavian agitprop. And while the Physical Culture Movement might be consigned to the past, football managers are still trying to convince ego-maniacs like Fabris to be team players. ◘

–––––

Extra time

- Sadly, at the time of writing, Plavi 9 is near-impossible to see. I was lucky enough to catch an online screening put on by Association des Cinémathèques Européennes in 2022. Barely any information about the film exists, but we do broadly know filming locations thanks to IMDb: the Croatian cities of Rijeka, Split and Zagreb, and Belgrade, Serbia.

- Though never explicitly referenced, the blue-kitted ‘Dinamo’ team in Plavi 9 is a facsimile of Croatian club GNK Dinamo Zagreb – director Golik was born in Zagreb and was likely a fan. However, the stadium at which the match action was filmed appears to be Partizan Stadium in Belgrade (I believe you can see the Saint Archangel Gabriel Serbian Orthodox Church in the background of the shot below). Like Plavi 9, the stadium has socialist origins. It was built in part by the Yugoslav People’s Army between 1948 and 1951, and officially opened on Yugoslav People’s Army Day in December 1951 – though matches were played there before then; perhaps some of the Plavi 9 footage is from the stadium’s first ever game, a 1-1 draw between Yugoslavia and France in October 1949. Initially home to the Yugoslav national team and Belgrade club Metalac (which became BFK Beograd, now OFK Beograd), today Partizan Stadium hosts Serbian Super League side FK Partizan.

Notice the church poking out from the top of the stands at Partizan Stadium, above in Plavi 9 and below in a photo from 2022.

Image from stadiony.net – not used for commercial purposes.